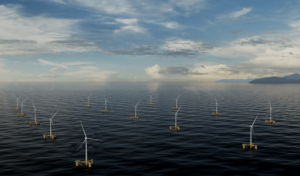

Odfjell Oceanwind is a floating offshore wind specialist developing technologies and solutions for floating offshore wind in the ocean. It is a key part of the Odfjell maritime industrial group, alongside its affiliated companies Odfjell Drilling and Odfjell Technology. Together, this group has operated in the energy service sector for five decades, becoming global leaders in offshore drilling in harsh environments with more than 5,000 employees.

“We are constantly bringing new technology to the market that pushes the borders of what can be done in the offshore space,” says Per Lund, CEO of Odfjell Oceanwind. “Of course, so far that technology has been developed for and focused on oil and gas drilling. Odfjell Drilling is a global number one when it comes to operating in harsh environments. Offshore drilling rigs working for the most demanding clients in the most challenging areas of the world, not only in the North Sea but in places such as Canada and South Africa.”

But while much of its technology and techniques have been developed for the oil and gas sector, Odfjell is now bringing that expertise to bear in the renewables space.

“We develop solutions that can carry the largest wind turbines that exist and deploy them to challenging locations in offshore environments,” Lund explains. “That is an ongoing journey that the whole offshore wind space is going through. We are pushing the limits as a front runner and pioneer in developing and mastering those kinds of solutions.”

A Three-Pronged Attack

For offshore wind farms to be a viable power solution, however, several key things need to change.

“First of all we need to reduce the costs of floating offshore wind, because it’s relatively expensive compared to other renewable energy sources,” Lund points out. “Secondly, we need to be able to deploy the solutions at scale.”

“At scale” for Odfjell means achieving its goal of delivering a gigawatt-scale project within a two year period. Currently the largest wind turbine generators available for floating offshore wind are 15 mw each, however 20 mw turbines are expected to be the standard by the early 2030’s, meaning the company will have to deploy 50 floating units to an offshore location in two years.”

Finally, renewable energy is not a project Odfjell is embarking on for the sake of it, so the impact of the wind farm must be carefully monitored.

“We need to be able to do this with minimum negative impact on people, workers, fishermen and other ocean activities as well as nature, marine life, and climate,” Lund tells us.

To achieve its goals, Odfjell needs to overcome all three of these challenges simultaneously.

As Lund says, “Driving down costs is a challenge, and to deliver these projects at industrial scale is something that’s never been done in any other industry before. We are doing this to deliver more renewable energy to mitigate the climate crisis, so we need to do so in a responsible way with minimum CO2 emissions or harming nature.”

Industrialising Wind

To achieve these goals, Odfjell will need to completely overhaul the entire way wind farms are manufactured and constructed. As Lund says, “We need to develop feasible solutions that will actually work in these harsh environments.”

Two key pillars of that strategy are standardisation and industrialisation of all parts of the project delivery value chain. The company has clear plans for establishing mass production, working closely with the supply chain to establish a highly industrialised value chain to meet these challenges.

“We have enforced a strict standardisation philosophy, using standard products in these wind parks, not bespoke pieces,” Lund says. “You need to think more like a car manufacturer than a one-off oil and gas project.”

This approach serves the twin purposes of bringing down costs while helping Odfjell achieve new levels of scale.

“We are going to deploy 50 units in two seasons. We are talking about doing this in harsh environments,” Lund says. “One of our core markets is the North Atlantic, so for practical purposes, we want to restrict offshore installation to the summer seasons.

That gives us 12 months in total, deploying one unit a week, so the logistic challenge there is immense. We have to think like a long production line, where you need a lean execution and supply chain at the same time as high quality. Any problems will clog up the project execution process.”

That gives us 12 months in total, deploying one unit a week, so the logistic challenge there is immense. We have to think like a long production line, where you need a lean execution and supply chain at the same time as high quality. Any problems will clog up the project execution process.”

While many of the methods and tools are new or in the process of being developed, Odfjell is also building on its existing expertise. The oil and gas business has long experience from managing potential conflict of interests with other activities in the ocean like fisheries and shipping, as well as planning for minimum impact on marine and bird life. This is all handled through active dialogue with relevant stakeholders and proper environmental impact assessments.”

“It means selecting the right locations, and selecting solutions that have a minimum impact on marine life related to noise and light,” Lund says. “It is also about participating in research to try to better understand the challenges and opportunities. Finally, on climate, we implement low emission solutions in all parts of the value chain as well as finding circular solutions where we can reuse and recycle as high portion of our assets as possible.”

The Best Option

Lund is the first to point out that constructing an offshore wind farm is costly, requires tremendous scale, and takes place in one of the most difficult and hazardous environments you can imagine working in. One could be forgiven for asking why anyone would want to attempt this in the first place.

“We all agree that to achieve our climate ambitions, we need more renewable power,” Lund says. “For a continent like Europe, the alternatives we have include hydropower, which is limited by access to waters and water systems, and of course the difference in altitude you would need. You would need mountains, so it is a limited resource. Solar power requires a lot of land area and Europe is the most densely populated continent in the world, so area is also a source of conflict.”

Even looking at alternative wind power solutions, the options are limited.

“Onshore wind has been developed and uses a lot of area with all of the conflicts involved. We have started to develop shallow water and bottom fixed wind parks, but we are about to have used all of the shallow water areas in Europe too,” Lund says.

“This is all driving us out onto deeper waters in the North Atlantic region, which has some of the best wind resources in the world. We are convinced that we will have to harvest that energy if we want to deliver on our climate ambitions. Basically, there are not that many other places to go if you want to replace a carbon society with renewable energy.”

Despite the challenges, offshore wind power is a solution that Lund is optimistic about.

“We are looking to have our first wind park in the water in 2026 and we are actively pursuing projects including larger utility-scale wind park opportunities across Europe,” Lund says. “This industry is in its infancy. So far we have only seen a handful of floating offshore wind projects. Our ambition is to be a global pioneer and leader in this space, starting in our home market in the North Sea and making the technologies and solutions in our home market available to projects worldwide.”