In October 1986, the two nations of Lesotho and South Africa came together to sign a treaty that would have long term benefits for both nations. It was a project to harness the power of the Senqu River and its tributaries towards two goals. Firstly, it would divert water from the river naturally going south towards the Northern Provinces of South Africa. The second goal was that along the way, it would pass through a hydropower plant, generating energy for the nation of Lesotho.

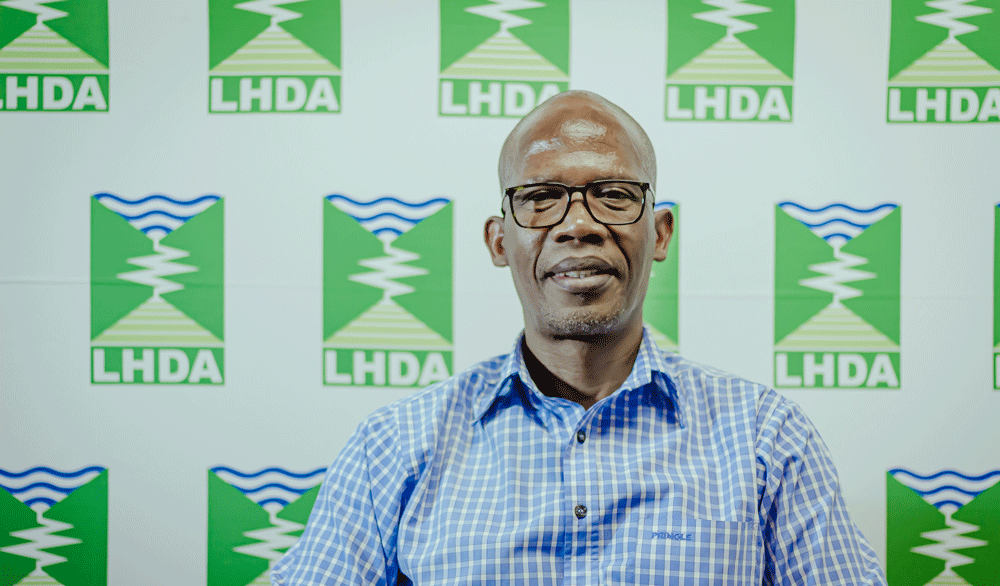

“It is intended to be a four-phase project, with each phase being implemented following an agreement between both countries,” says Reentseng Molapo, Divisional Manager for Development and Operations at Lesotho Highlands Development Authority, the implementing authority for Lesotho’s part in the project. “To date we have implemented the first phase in the project, which was completed around 2004, and we are now implementing Phase II, which began work around 2013 following the signing of the Phase II agreement.”

That might seem like a long time for a project to be underway. This is because of the enormous scale of the work that is being carried out, and the prerequisites laid out in that original agreement in 1986.

“The treaty indicated that each phase of the project should only be implemented on agreement of both countries,” Molapo says. “When Phase I was completed in 2004, both countries agreed to defer Phase II because the demand for water in South Africa was low enough that it was not yet required. Each phase will only come to implementation when it is actually needed. That is the uniqueness of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project.”

It is difficult to find any comparable project where sustainability and needs set the terms in such a clear manner. The patient approach required for a development of such a scale makes the Lesotho Highlands Water Project a unique undertaking.

“The agreement to implement the project is unique in that it clearly indicates the responsibilities of each country and what those responsibilities will be,” Molapo tells us. “For example, we are diverting the waters of the Senqu River for the benefit of South Africa, so South Africa is responsible for the infrastructure that diverts that water. They are funding the construction, operation and maintenance of the dams, tunnels and other related infrastructure.

Lesotho benefits by using the water to generate electricity as it goes into South Africa, and on top of that Lesotho benefits from the Royalties collected for the water that is diverted to South Africa. I have never come across a similar project anywhere in the world.”

Changing Course

Changing Course

Of course, a project of this scale and longevity, carried out across national boundaries, comes with its fair share of challenges.

“Each government has to fulfil its responsibilities and as the implementing agency in Lesotho we have to ensure that each party is aware of its obligation at any given time,” says Molapo. “We have to communicate effectively through the responsible authorities with each government. The wheels of governments can turn slowly, but when you are implementing a project like this, you might need very quick decisions. So, there can be challenges and delays if decisions are not made quickly, but we try to anticipate those challenges and put risk mitigations in place.”

As well as challenges around communication, the binational nature of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project also presents legislative challenges.

“You may find that the Treaty and the Phase II agreement have an impact on different regulations and laws on each side of the border, so those need to be identified early on and highlighted to the two governments” Molapo points out.

Finally, with a project of this scale, the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority has to remain hyper-aware of the wider impact its work may have.

“We are constantly looking at the impact that we have on the communities and the environment when we build this kind of infrastructure,” Molapo tells us. “That is one of the major priorities when we are implementing this project. Stakeholder engagement and consultation, alongside community engagement and consultation, are required on a regular basis to make sure that wherever communities are affected they understand how they will be affected, and how they will be compensated, and agree to it, so the project can be implemented smoothly.”

Currently, the biggest undertaking facing the project Operations and Maintenance (O&M) is a six-month stoppage of water transfer and electricity generation to meet maintenance requirements.

“At a minimum of every five years, as prescribed by our O&M manuals, we stop the water transfer going into the tunnel to carry out maintenance inspections and determine whether the systems are still in good condition to operate for another ten years,” Molapo says. “We last did this in 2019 and determined that the tunnel’s linings were having levels of corrosion that meant the steel linings needed to be refurbished and applied anew to ensure continued, safe operation. We are currently in the middle of that project.”

While the water transfer and hydropower generation have ground to a halt for six months, Molapo forecasts it will ensure the integrity of the infrastructure for another 20 to 30 years. But it still places the project on a tight schedule.

“It is important that this six-month outage is completed within the allotted time because it means we are currently not transferring any water to South Africa or generating electricity,” Molapo says. “This six months has an impact on current water supply even as it assures that supply for the future.”

To mitigate that impact, extra water has been transferred through the project ahead of the outage, and more will be transferred after. This also ensures that revenue from Royalties to Lesotho is not impacted too adversely for the year.

The Next Phase

The Next Phase

As for the third phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project – while it may come, it will not be according to any strict timetable. As before, every stage depends on the agreement of all parties to get underway.

“The current phase of development is intended to be completed in 2028 or 2029, but there are already efforts to have the two governments talk about the implementation of Phase III. When the treaty was signed all four phases of the project were agreed to be completed by 2044, and it is up to the two governments to decide whether to extend the project and the treaty that governs it. So, we still have some time.”